It was in the United States during the 1960s that intergenerational programmes - "initiatives or programmes that increased cooperation, interaction and intergenerational exchange" - first had an impact (Foster Grandparents was an IP developed and implemented in the United States in 1965, during the presidency of Lyndon Johnson) [i] . During the next four decades, intergenerational programmes have demonstrated their effectiveness in tackling social issues such as: ethnic and racial prejudice; ageism and social isolation. They are social tools that foster positive change in the way that different generations perceive each other. They increase empathy toward older people, and promote with the transfer of knowledge and skills. Despite all the positive evidence for intergenerational programmes, however, it seems that many of them - even when they are acknowledged to work well - are relatively short-lived [ii]. Thinking about the sustainability of intergenerational programmes therefore, an obvious question arises: why do excellent intergenerational programmes have an average duration of only two years?

In an attempt to tackle this question, I conducted a qualitative study of the sustainability of intergenerational programmes in Portugal, with a special focus on programmes implemented in educational settings. The field work was carried out in nine municipalities in Grande Porto, where I was put in touch with programme managers in schools by local government officials, and eventually selected seven examples of intergenerational programmes for case studies. Since the voices and views of programme managers have not been so well represented in the research literature as those of the main client groups, youths and seniors, I decided to make their narratives the centrepiece of my enquiry into the conditions for sustainability in intergenerational programming.

The main findings of the study were in line with recent international work. It has been argued, for example, that there is a need to "promote sustainability" in order to fill the "lack of financing and training of professionals" and the lack of interinstitutional partnerships [iii]. For this blog post I will only focus on the lack of training for intergenerational professionals. The results of the study highlighted a lack of training of the programmes managers, specifically in respect of the intergenerational aspect of their work - the requirement to work with young people and seniors together. The managers themselves, however, did not think that there was any kind of significant gap in their training. From their point of view, the fact that they had a degree in a social sciences discipline and work experience with one of the generations, either young people or seniors, gave them the qualifications and confidence needed to implement an intergenerational programme. They are not expected to have had any specifically intergenerational training, and because Portugal, unlike other European countries, does not offer any such training opportunities, the absence of this additional component in their training strikes them as normal.

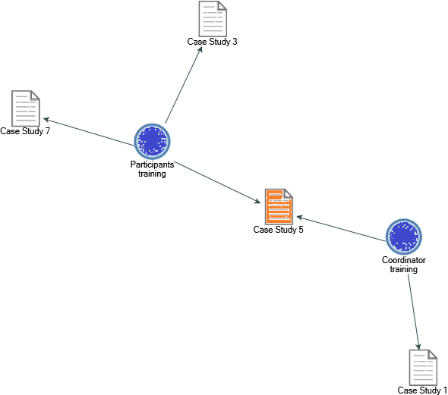

The following diagram shows the relationship between the training of the intergenerational professionals and the training that they themselves provide or not to the participants before and during the intergenerational programme.

Relationship between coordinator training and participant training in four case studies

Source: Azevedo (2017)[iv]

The challenge of providing training opportunities for the intergenerational professionals is important not only as a research question in this particular study, but also as a practical problem that arises for intergenerational programming in Portugal. As can be seen from the comparison diagram, the association between the programme manager’s training and the participants’ training opportunities is not feasible. These two dimensions seem to be associated only with the case studies 5. Hence, a programme manager that does not value his/hers own training will not value training opportunities for the programme’s participants. A possible explanation could be that the deficits found in the IPs, in terms of sustainability, are explained by the shortcomings in the training of the coordinators. In fact, the only case study that achieves an association between the two dimensions was the coordinator who relied on a consultancy from an academic institution.

Adequate training for intergenerational programme managers requires an understanding, based on scientific knowledge, of the needs and capacities of both generations. What is needed in the training is a relational focus. Fostering relations between the generations is after all the ultimate goal of any intergenerational programme. Even though the international IP literature presents and recommends training programs designed exclusively for intergenerational programmes managers (e. g., Certificate of Intergenerational Projects) and a variety of manuals for intergenerational programming [v], intergenerational work in Portugal is hampered by a lack of proper training opportunities for intergenerational professionals (and this includes manuals on implementing an intergenerational programme in Portugese). Examples of good practice of intergenerational training opportunities can be found in United Kingdom and Spain. In both countries training opportunities are provided on a regular basis, at least twice a year, and several published guides are available - in English and Spanish - to help professionals to design, implemented and evaluated an intergenerational programming.

References

[i] NCOA (1981) The White House Conference on Ageing “Strategies for Linking the Generations”. National Council on Ageing. Washington, DC.

[ii] Marx, M. S., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Renaudat, K., Libin, A. & Thein, K. (2005) Technology-Mediated versus Face-to-Face Intergenerational Programming, Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 3:3, 101-118, DOI: 10.1300/J194v03n03_07.

[iii] Jarrott, S. E., Morris, M. M., Burnett, A. J., Stauffer, D., Stremmel, A. S. & Gigliotti, C. M. (2011) Creating Community Capacity at a Shared Site Intergenerational Program: “Like a Barefoot Climb Up a Mountain”. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 9(4), 418-434, DOI: 10.1080/15350770.2011.619925.

[iv] Azevedo, C. (2017) Programas de Educação Intergeracional Sustentáveis: desafios atuais e perspetivas futuras . Tese de doutoramento. Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar, Universidade do Porto.

[v] Bressler, J., Henkin, N., & Adler, M. (2005) Connecting generations, strengthening communities: A toolkit for intergenerational program planners. Philadelphia, PA: Intergenerational program planners. Center for Intergenerational Learning. Epstein, A. S. & Boisvert C. (2006) Let's Do Something Together. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 4:3, 87-109. Newman, S., Ward, C. R., Smith, T. B., Wilson, J. O., & McCrea, J. M. (Eds.), (1997) Intergenerational Programs. Past, Present and Future. Taylor & Francis. Washington, DC. Steinig, S. (Ed.) (2005) Under one roof: A guide to starting and strengthening intergenerational shared site programs. Washington, DC: Generations United.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.