The Human Development Index and the Corruption Perceptions Index are two well-known examples of composite indicators that are used both to produce international rankings of country performance, and to measure progress over time. Although composite indicators sometimes come in for a bit of stick (see article in Economist), they have been become very popular among policy analysts and have extended their reach over more and more policy domains.

They measure performance in policy domains where measurement – if it is to have any credibility at all – has to be multi-dimensional. The ‘trick’ is to combine several indicators into a single metric that is reasonably easy to understand and acceptable as a measure of performance in a complex policy domain. They can be a good way of driving change in policy, and they are often very good at attracting the attention of news media. Some acquire authority; many do not. It depends on whether and how they are used by the research and policy communities.

There are now a great many composite indicators available as a source of international rankings, and they vary in quality. It matters whether or not there is a solid idea that makes sense of the aggregation of multi-dimensional data into a single metric (e.g. Sen’s ideas about capabilities). No less important is the quality of the data that goes into the indicator, and finally they have to be methodologically sound. Even when they satisfy all these criteria, they may be open to misuse and misinterpretation. The very fact, for example, that they present results in the form of country rankings can give undue weight to small differences in the metric that underlies them.

Since composite indicators are now constructed to assess performance in all sorts of policy domains, it should be no surprise that there are several that ought to engage the attention of students of population ageing. In the last couple of years, for example, two different attempts have been made to construct a composite indicator for intergenerational justice – one from the UK Intergenerational Foundation which purports to measure progress in the UK, and one from the European Centre for Social Welfare Research which compares performance across OECD countries. There is a Global Pension Index to compare the effectiveness of pension policy in different countries. HelpAge International produce the Global Age Watch Index to compare how older people fare in countries across the globe.

Of more immediate relevance to my own current work is the Active Ageing Index which is compiled with the support of the European Commission and UNECE. The idea to develop such an index evolved from the Madrid Action Plan on Ageing, and was given its final shape by the European Year for Active Ageing (2012).

The aim is to focus on the role that older people play in society – not as potential recipients of services and support, but rather as active contributors to economic and social life. In spite of the evidence linking some forms of activity with certain aspects of well-being, it is not a measure of well-being or welfare (unlike the Age Watch Index). This should be evident in the use made of employment data in the index. High employment rates at older ages undoubtedly tell us something about productive activity in the older population; they do not tell us whether continuing engagement in the labour market should be understood ‘as a positive choice’ or rather as an unwelcome necessity forced on individuals by their circumstances. The fact that both Romania and Sweden have high employment rates in their 65+ population does not mean that the reasons for continuing engagement in the labour market are the same. By the same token we should not suppose that high scores are a clear marker for policy success. Active ageing is something that governments should try to promote, but it surely matters how they achieve it.

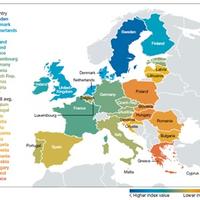

A country’s readiness to meet the challenges associated with demographic ageing may be assessed and measured from several different points of view. What the Active Ageing Index aims to provide – for Europe only - is one such point of view. It integrates data that provide answers to three key questions. To what extent is the older population socially - and not just economically – productive? To what extent are older people able to live independently? How successful is the society in sustaining or improving the human capital that is embodied in the older population? The map below displays the results (for 2014) of combining data for indicators that can provide answers to these questions into a single metric.

Map of active ageing scores in Europe

The Institute is currently supporting work to develop and promote the index by collaborating on the production of an edited volume of papers from an international workshop in Brussels earlier this year, as well as a special themed edition of the Journal of Population Ageing.

About the Author:

Kenneth Howse is a Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing. He is also a key member of The Collen Programme on Fertility, Education and the Environment.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.