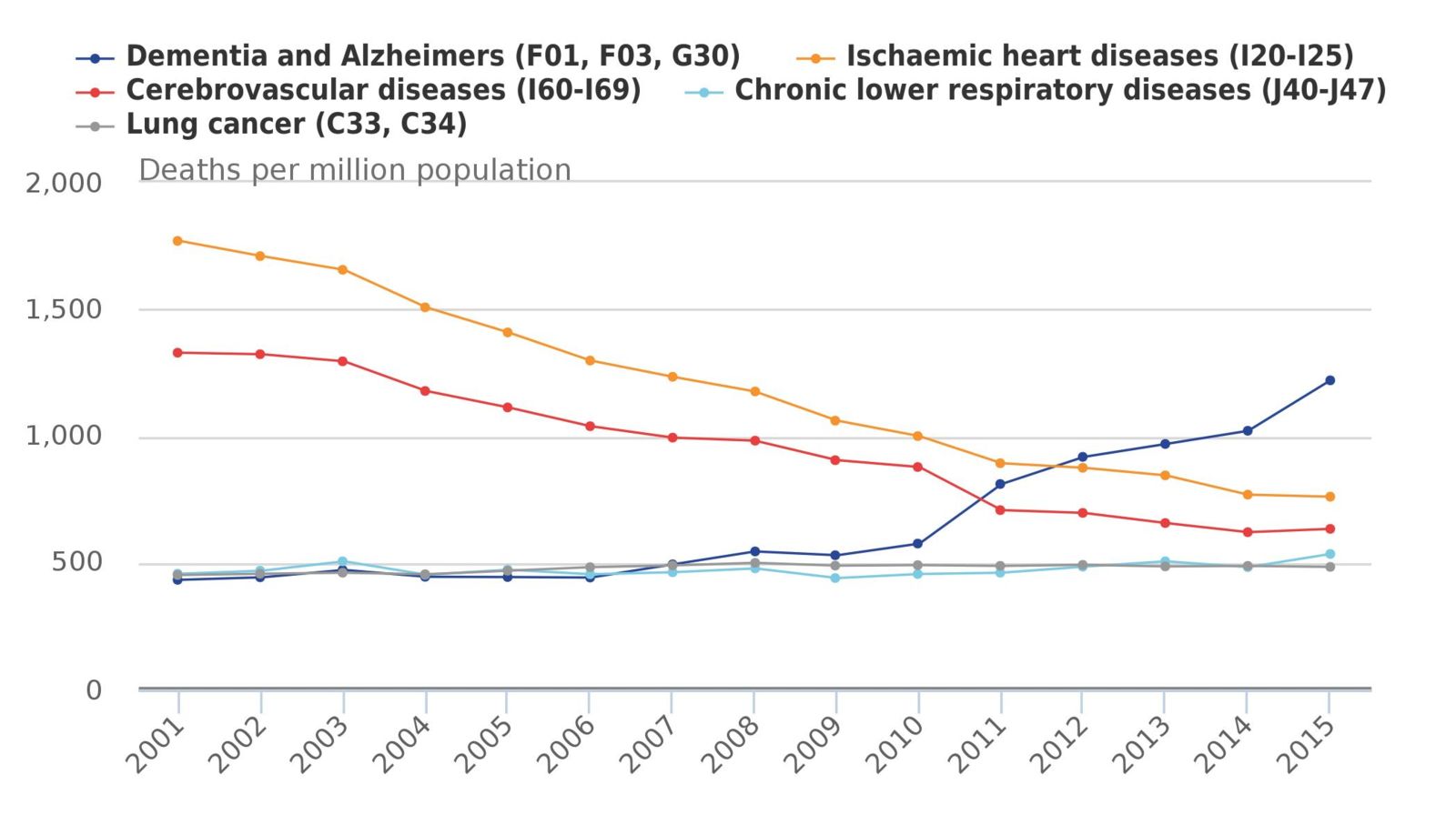

A statistical bulletin released by ONS last week reported that in 2015 Alzheimer’s Disease and other dementias were the leading cause of death in England and Wales. As the bulletin explained, more people die from cancer – if all cancers are treated as a group, and the same goes for what is usually termed circulatory disease, which combines deaths from all forms of heart disease and stroke. In 2015, as in 2014, circulatory disease was the second main ‘broad cause’ of death after cancer. The fact that there may appear to be little change at this level of analysis (‘broad causes’) can however obscure the importance of changes that are happening at a lower level of analysis which treats e.g. different cancers as well as ischaemic heart disease and stroke as distinct causes of death. Hence the significance of the most recent bulletin: whereas in 2014 ischaemic heart disease was the most common cause of death at the more specific level of analysis, followed by dementias (considered together as a connected group of degenerative diseases of the brain), in 2015 this ordering was reversed.

The interpretation of these data, as the ONS acknowledges, is not straightforward. Although the increasing prominence of dementia as a cause of death does indeed point to major changes in patterns of late life chronic disease – with a lot more people surviving to ages at which the risk of dementia starts to increase quite dramatically – it is important to recognise that changes in recorded causes of death sometimes reflect changes in reporting practice quite as much as changes in underlying epidemiology, and in this instance there is good reason to think that this is indeed a substantial part of the story. Consider, as an exhibit, the behaviour of the trend line for dementia and Alzheimers in the chart below: something happened in 2010-11 to kick off a continuing increase in recorded deaths among women.

Figure 1: Age standardised death rates in women 2015

One point to note about these data is that they start in 2001. The year is important because it means that the data series begins at the same time as the introduction of a new classification of diseases for the coding of deaths (ICD-10 to replace ICD-9), and alongside the introduction of ICD-10 was new guidance on the application of one of the WHO rules for selecting the ‘underlying cause of death’ – the so-called Rule 3. Conditions that would previously have been mentioned on the death certificate as ‘contributory causes’ of death (but not ‘related to the disease or condition which caused it’) would henceforth be selected as the ‘underlying cause of death’ if the immediate cause of death was obviously a consequence of that condition. This effect of this regulatory shift was to reduce the number of deaths assigned to conditions such as pneumonia and increase the number of deaths assigned to chronic debilitating diseases, and in the UK, where a large number of death had previously been attributed to pneumonia under ICD-9 (about 20%), the impact on the mortality data was considerable (see Health Statistics Quarterly no. 13, 2002).

The ONS data series also post-dates the emergence of a growing propensity among physicians “in a large number of north western European countries in the 1980s and 1990s” to report dementia as the underlying cause of death (Jansen & Kunst 2004). It used to be widely accepted, among physicians as well as the public, that although many people died with dementia, it was very uncommon for people to die of dementia. It was taken for granted that the underlying cause of death would almost always be something else, and this is what would be recorded on the death certificate. Dementia was typically assigned no significant role in the causal sequence that led to death; if mentioned at all, it was included as a contributory cause. This started to change in the 1980s, and AD and other dementias were increasingly recognised to be potentially fatal diseases. Chronic debilitating diseases eventually lead to frailty, and frailty – by definition – involves increasing vulnerability to health shocks. In other words, for some people who die with dementia, dementia will also be the underlying cause of death, and if more people survive longer with dementia - so that their condition becomes more advanced – it becomes increasingly plausible to see it as the underlying cause of death.

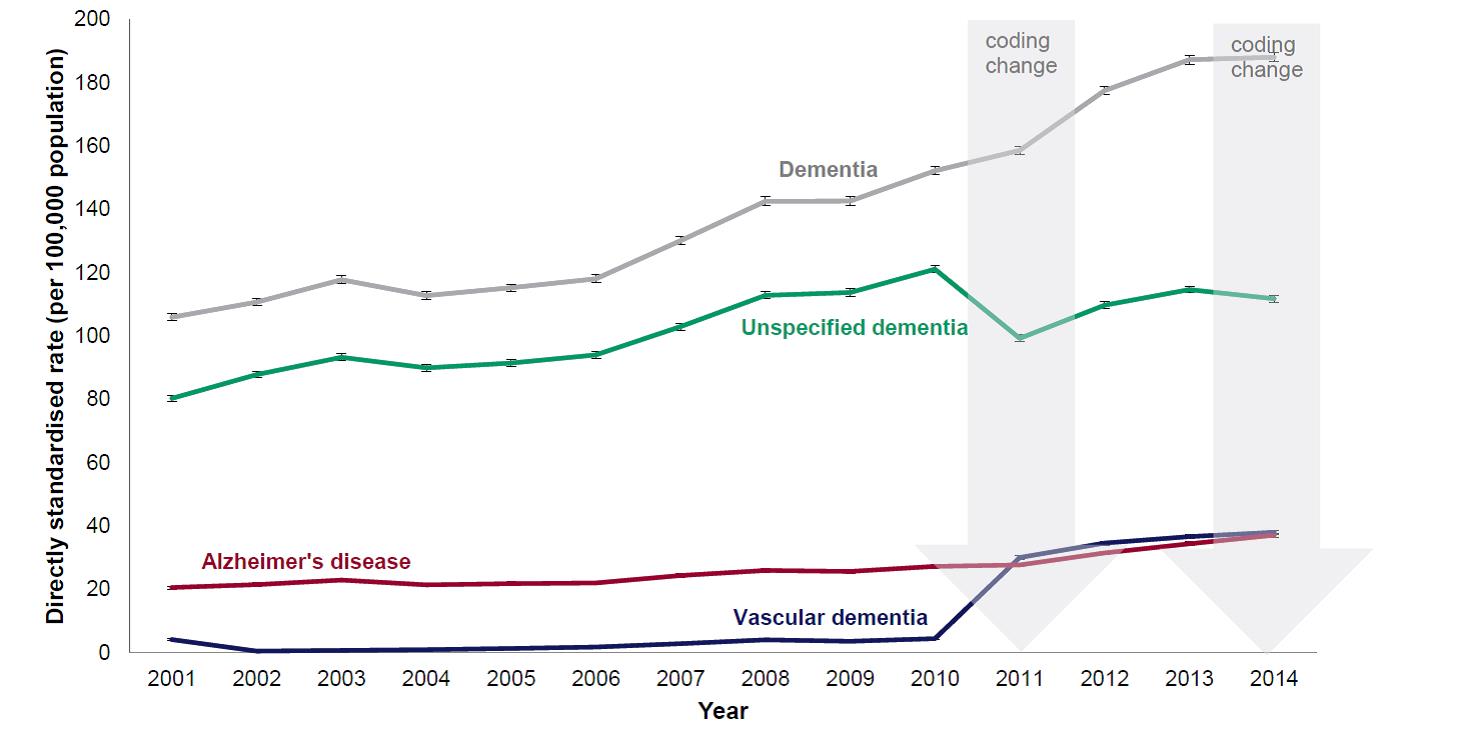

A final note on post-2001 changes in reporting and coding: some of the increase between 2001 and 2015 should be attributed to the increasing awareness of dementia among physicians and the implementation of policies to increase the dementia diagnosis rate. If more people are being recognised as dying with dementia, it is highly likely that dementia will appear more frequently as the underlying cause of death. There have also been changes in coding practice since 2001, including two changes (2011 and 2014) in the software that is used for automated coding. The 2011 change affected the selection of vascular dementia rather than ‘cerebrovascular disease (unspecified)’ as underlying cause of death in many older people with dementia.

Figure 2: The directly age standardised mortality rate for deaths with any mention of dementia by subtypes, persons aged 20 and over, England, 2001-2014

About the Author:

Kenneth Howse is a Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing. He is also a key member of The Collen Programme on Fertility, Education and the Environment.

Comments Welcome:

We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.