In 1906 Francis Galton visited the West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition, a country fair in Plymouth, where he witnessed a competition to guess the weight of a fat ox. For a sixpence, the fairgoers - a mix of butchers, farmers, and others willing to take on the wager - would estimate the animal’s slaughtered weight in the hope of winning the prize. After the competition, the Victorian statistician managed to get a hold of the almost 800 tickets with their estimates “unbiased by passion and uninfluenced by oratory and the like” and proceeded to analyse the distribution of guesses. To his great surprise, the median value of the guesses was 9 lbs from the true value, a finding he reported in a Nature article under the title Vox Populi (html version).[1]

Finding the true weight of the ox is a relatively straightforward thing to accomplish - although finding its slaughtered weight is unfortunately a rather more involved procedure - compared to finding the truth value of many propositions we encounter daily. The idea of using some form of gambling to assess the likelihood of certain findings being true, or future events coming to pass, is by no means new, but it is, I would argue, underutilized. Perhaps it is frowned upon, and certainly in some jurisdictions it is explicitly illegal. Still, there are some nice examples of its use in more recent times and hopeful signs of it becoming more common, as well as suggestions of linking some types of prediction markets into the academic process! And if you have moral misgivings about gambling, no spare cash, or are simply reluctant to stake your reputation publicly, you can still engage in a prediction exercise privately, see how much better you are than random chance, and recalibrate accordingly.

Individual bets

One of my all-time favourites as a serious bet on the future is the Julian Simon – Paul Ehrlich bet of 1980-90. Their disagreement was over the limits to growth on our planet, with Simon the cornucopian arguing that human ingenuity is the Ultimate Resource, and Ehrlich, the “neo-Malthusian” author of the Population Bomb, arguing that population growth will inevitably result in resource scarcity, which should manifest itself in price increases imminently. They decided to adjudicate their positions with a carefully defined wager on the prices of five “non-government controlled raw materials” in 10 years’ time. The bet was won by Simon as the average price went down by over 50 percent over the agreed period, even though the 80s were the decade of the largest population increase in history. Ehrlich paid up, but dismissed the bet as unimportant and to this day continues to predict imminent population-related disasters.[2]

Other similar wagers have been made publicly, for example the Simmons–Tierney bet on the price of oil 2005-2010, in which Tierney’s[3] cornucopian position won him $5,000. Commodity prices are an easy betting metric (and these two bets essentially amount to futures trading for a bit of money and a bit more reputation) but scientific wagers are of course not limited to resource economists. There is for example the bet International Chess Master David Levy made in 1968 against two prematurely optimistic artificial intelligence researchers, McCarthy and Michie, that no computer programme would beat him in the following 10 years, which netted him £1,250. Or the Kip Thorne and Stephen Hawking on the one side, and John Preskill on the other bet on the black hole information paradox (which I will not attempt to pretend to explain, but am somewhat comforted by the fact that it seems even the three of them do not agree on the outcome of the bet).

In addition to bets between individuals, there is also the category of one-sided challenges. One of the most famous of these is the James Randi $1,000,000 paranormal challenge, which started in 1964 as an offer of £1,000 to anyone who could “demonstrate a supernatural or paranormal ability under agreed-upon scientific testing criteria”. 51 years and cca. one thousand unsuccessful challengers later, the un-awarded million dollar prize was transformed into a grant-making foundation just last year, when Randi retired from his position. What has the challenge accomplished? Perhaps something similar to the Simon-Ehrlich bet: one side interprets it as proof that no supernatural abilities exist, hence no one was ever able to claim the reward, while the other side sees it as a rigged contest, and their lack of success as irrelevant to their claims.

The website longbets.org provides one online platform for such bets and predictions (although the proceeds of the bets must be donated to the winner’s preferred charity, since otherwise the website would fall foul of US gambling laws). There is for example an ongoing $1,000 bet that the Large Hadron Collider will destroy the Earth by 2018, and in case it does, the winnings will be donated to the National Rifle Association (as opposed to Save the Children if it doesn't). Strangely no-one has yet challenged the 2009 prediction that world population will peak at or below 8 billion by 2050, so if you have a charity in mind, you can try to publicly state the obvious (although the predictor may now refuse to accept your challenge).

Prediction markets

While UK bookmakers have increasingly started accepting bets on non-sporting events such as election results, the discovery of Higgs boson or royal baby names, the odds that are given cannot easily be converted to probability predictions of an event occurring. That is because they are calculated by in-house risk analysts so as to take into account expert knowledge about the event, as well as the betting behaviour of the punters. They are trying, after all, not only to balance their books, but also to make a decent profit.

Fig; 1: Neutrinos by Randall Munroe.

Prediction markets on the other hand eliminate the bookies by allowing punters to play directly against each other by trading on the likelihood of various events. The market price then emerges as a direct indicator of the participants’ estimated likelihood of an event. These markets not only aggregate public opinion, but the price discovery mechanism means that people’s confidence is directly taken into account by the amount of money they are willing to stake. This is supported both by theoretical as well as empirical research.

Perhaps one of the best known prediction markets was Dublin-based Intrade, an online exchange that operated for almost 15 years, closing down in 2013. The year before, it was forced to stop trading with US customers after the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission filed a lawsuit against the company because its activities constituted gaming. As Americans were the main customer base for Intrade, that effectively precipitated its closure in the following year. The blurry line between gambling and information discovery that lead to Intrade’s demise is particularly tragic in light of the remarkably accurate predictions it generated (in markets where trading volume was sufficiently high).

A more recent New Zealand startup Predictit may partly take its place, having secured the CFTC’s approval on the condition that the “investments” are limited to $850 and no more than 5,000 traders are allowed to bet on a single question. The site currently features almost exclusively political bets, whereas Intrade’s remit additionally covered entertainment, science, current events such as bird flu and earthquakes; it even had a sub-platform that allowed users to create their own markets.

Over 25 years ago Robin Hanson first proposed and elaborated on the idea of using prediction markets as a method of establishing consensus on scientific questions in the paper Could gambling save science? Encouraging an honest consensus. In his own words:

“Imagine a betting pool or market on most disputed science questions, with the going odds available to the popular media, and treated socially as the current academic consensus. Imagine that academics are expected to "put up or shut up" and accompany claims with at least token bets, and that statistics are collected on how well people do. Imagine that funding agencies subsidize pools on questions of interest to them, and that research labs pay for much of their research with winnings from previous pools. And imagine that anyone could play, either to take a stand on an important issue, or to insure against technological risk.”

A tentative step in that direction was recently made in the context of Brian Nosek's Reproducibility Project in Psychology, a massive enterprise attempting to reproduce 100 published experiments in psychology. It was the perfect project to test out the idea behavioural economist Anna Dreber and colleagues came up with in a bar: to use a prediction market “to estimate the reproducibility of scientific research”. Which is essentially a euphemism meaning “to determine if the findings are true or not”.

Their paper published just two months ago describes recruiting 92 participants and giving them $100 each to buy and sell stocks of 41 studies from the reproducibility project. The starting price was $0.50, and as trading progressed, the prices reflected more and more the consensus of the participants on whether or not the results would replicate in the repeat experiments organized by Nosek's team. The market correctly predicted 71 % of the outcomes, statistically significantly better than the survey amongst the participants before trading started (58%).

While this may not seem like a dramatically high result, you should keep in mind that these were all published and peer-reviewed studies and the implicit assumption is therefore that they are true within the margin of statistical significance. Nosek's team found surprisingly that only 36 of the 100 replicated experiments produced significant results, and Dreber's market participants were similarly pessimistic, reckoning that about half would replicate. Or as Dreber succinctly puts it:

“What's going on with peer review? If people know which results are really not likely to be real, why are they allowing them to be published?”

Robin Hanson's reaction to what could easily be seen as a corroboration of his 1990 manifesto was measured to say the least: prediction markets' superiority has already been well established, but as long as there are no stronger incentives for academics to take part in these markets than personal curiosity, they will unfortunately not become standard academic practice. The push will have to come from either financial incentives or the standard requirement for people's trading records on job and grant applications, or their use in publication decisions. And until that happens, perhaps the bragging rights that come with a good record of publicly made predictions are a first step in that direction.

Betting against yourself 2016

I know it’s already mid-January, but on the off chance that you have any New-Year’s resolutions left intact, you may want to increase your chances of sticking to them by following Zelda Gamson’s example, who explained in a RadioLab episode how she quit smoking by promising to donate $5,000 to the Ku Klux Klan if she ever lit up again. And the idea of them having her money was powerful enough to overpower any cigarette cravings in the subsequent 30 years.

But what if you don't want to risk your money? Not even your reputation? You can still play against yourself by writing down any predictions that come to your mind, assigning them probabilities, and then simply waiting. Or test yourself by making (free) predictions on the new metaculus website, and develop your predicting skills. How do you think you will compare with Scott Alexander of slatestarcodex.com, who publicly makes annual predictions about world events and his personal life, along with assigning them confidence levels and then come January scores them against reality?

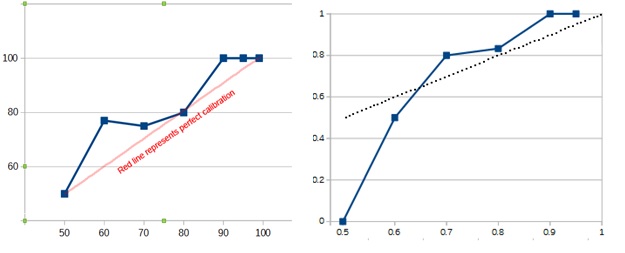

Fig: 2: Scott declares himself impressively calibrated in 2014 (left) and calls 2015 (right) another successful year.

Admittedly he sets a high bar, but presumably he has been calibrating himself for some time. Which is the least we could do: play against ourselves, no cheating, figure out just how bad our biases are and in which directions, and then recalibrate. And try again. And that's my resolution for 2016 (with a 70 % chance of following through).

[1] In fact the mean of the guesses was only 1lb shy of the true value - for an interesting debate about whether or not Galton knew this and why he preferred to report the median see the debate that developed on Robin Hanson’s blog back in 2007: Author Misreads Expert Re Crowds

[2] Several people have noted that Simon would have likely lost most other versions of the bet using a different basket of commodities and a different time frame – although he was the one to pick the basket used in the bet. See Paul Sabin’s excellent book the Bet for more, or listen to his interview with Russ Roberts on EconTalk.

[3] Ironically in the context of the the wisdom of crowds argument, Tierny's guiding principles are apparently “i) Just because an idea appeals to a lot of people doesn't mean it's wrong. ii) But that's a good working theory.”(Source: TiernyLab). Still, the argument is that if these people had to put money on it, you'd get a much better estimate of whether it really is wrong.

About the Author

Dr Maja Založnik s a demographer currently working on a joint project of the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing and the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.

_square_md.jpg)