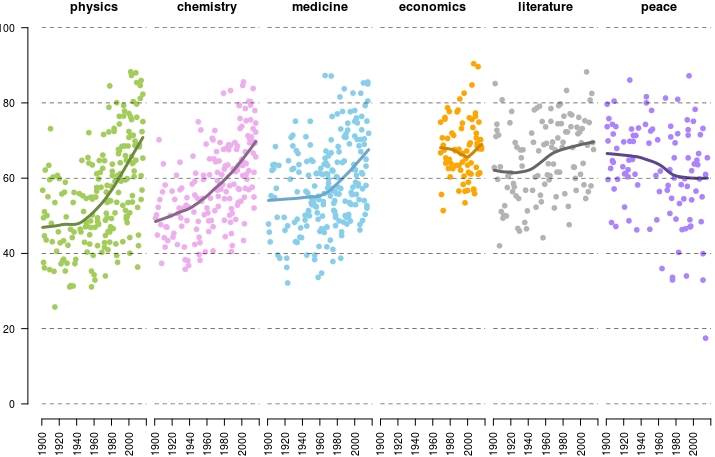

It is Nobel Prize awarding season, and with just one award to go – Literature is to be awarded on Thursday – it is also the season of pundits noticing the laureates have a remarkable tendency to be old men, and furthermore that their tendency to be old has also been increasing for decades. The Economist's daily chart summarised the data for the six prizes (the Economics prize is strictly speaking not a Nobel Prize, but having made the obligatory mention of this bit of trivia, I will cease with the nitpicking), with the trend especially obvious in Physics, Chemistry and Medicine, while Peace is the one clear outlier.

Since the data is freely available through the Nobel Prize API, it is easy to recreate the charts that have been doing the rounds with the most up-to-date winners and their birthdays (for obvious reasons I have excluded any prizes awarded to organizations). The sharply rising smoothed lines are particularly striking for Physics, Chemistry and Medicine, while being less so for Literature – although the latter's laureates had an older average to begin with.

Figure 1: Ages of all (human) Nobel laureates at time of award with smoothed line fitted (Source: Nobel Prize API)

Although Alfred Nobel stipulated the prizes should be awarded “to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind”, this requirement has been greatly relaxed in practice, at least in part because it takes longer for a consensus to emerge about how revolutionary a discovery in fact is. At the same time the statue prohibiting posthumous awards is being strictly adhered to, which means the selection committee might feel rushed to award prizes to people less likely to wait around for next year. The BBC similarly wondered whether this trend is due to the explosion of the amount of knowledge, or the ballooning of the number of scientists synthesising this knowledge into theories.

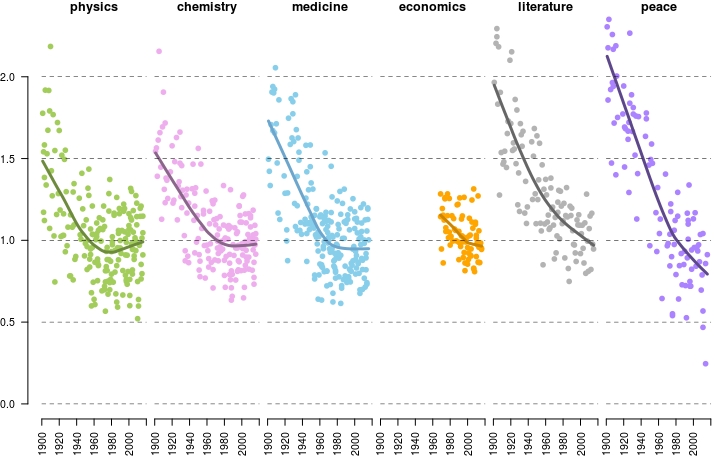

Although the reasons behind them may not be as clear as the trends themselves, we know of another, related, trend that has been even more dramatic over the past century: that of rising life expectancy. In what may well become my signature move (see my last post about the life expectancies of Brexit voters) I could not help but conduct a quick calculation to see how the increasing age of Nobel Prize winners holds up in relative terms: what proportion of the average lifespan are the laureates waiting before they get called to Stockholm (or Oslo)?

Global life expectancy (as compiled by the Max Roser at Our World in Data) has increased from just over 31 in 1901, the first year the prizes were awarded, to over 71 years today. This means the average Physics or Chemistry laureate at the beginning of the 20th century was 50% older than the average life expectancy at the time, and the average Literature laureate was over twice that age! As they grew older towards the mid century, life expectancy was increasing even faster, catching up only in the sixties. If we stick with the first three prizes on the left hand side of the chart, this is where the smoothed line evens out and becomes horizontal: the laureates are getting older, but the life expectancy is increasing as well to counter this almost exactly, except in Physics, where the scientists are getting older slightly faster than life expectancy can catch up with. Interestingly, in all the prizes except for Peace, it also seems that the average age of the winners ends up settling somewhere around 100% - i.e. at around the average global life expectancy.

Figure 2: Ages of all (human) Nobel laureates at time of award relative to the global life expectancy at the time. with smoothed line fitted (Source: author's calculations from Nobel Prize API and Our World in Data, analysis shared in this public repository)

With more detailed data it would be possible to match the winners' country of origin with that country's life expectancy data, and get a more specific measure of each individual winner's relative age when they won. Using global life expectancy instead is of course easier. But it is also conceptually more appropriate: these prizes are awarded for outstanding contributions for humanity. As a species we are facing global problems, and finding solutions that benefit mankind. And there is only one metric of life expectancy that can be relevant in this case, that of the species as a whole, of all the citizens of the world.

About the Author

Dr Maja Založnik s a demographer currently working on a joint project of the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing and the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food.

Comments Welcome:

We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.