Numerous controversial executive orders, memoranda and proclamations signed by US President Trump since his inauguration have left many people aghast and distraught, and the rate at which they are being announced barely affords us time to consider their implications before being faced with the next, even more disturbing and potentially unconstitutional decree.

In the grand scheme of things it therefore not surprising that the memorandum reinstating the so called Mexico City policy – a.k.a. The Global Gag Rule last week has already been relegated to the back burner. Especially since it is not a particularly idiosyncratic Trump move, but a rather more generic Republican president move. But I thought it would still be worth having a look at what we know about the policy, and what we might expect from it – especially given that this is already the third time it is being invoked, so we have presumably already learned something of its effects.

The policy - originally announced by the Reagan administration at the 1984 UN population conference in Mexico City - banned USAID funding of family planning organizations that do not explicitly reject abortion. The simplified version of the story is that ever since, each new US president has – depending on party affiliation - either rescinded or reinstated the policy within days of taking office. Clinton in 1993, Bush in 2001, Obama in 2009 and now most recently Trump in 2017. It thus looks like a particularly clean natural experiment, which should allow the effects of the policy to be assessed quite easily.

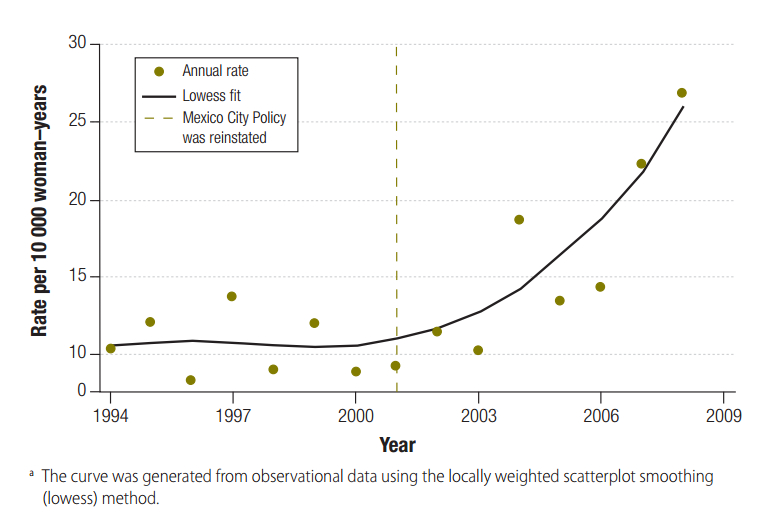

I was still surprised to find the following dramatic chart in a 2011 paper by Bendavid et al. looking at rates of induced abortion in sub-Saharan Africa before and after the second reinstating of the policy in 2001. There seems to be only one other empirical study, also showing robust effects of the policy increasing unwanted pregnancies, abortions and child malnutrition in Ghana (Jones 2011). The general consensus seems to be that the policy is not achieving its stated aim of reducing abortion numbers – but it should be noted that reliable quantitative studies remain rare since induced abortions are controversial even where completely legal and safely accessible, and good quality data is difficult to obtain. On the ground there is however no doubt: organizations have been forced to lay off staff, close clinics and cut services way beyond the policy's purview.

Figure 1: Induced abortion rates in 20 sub-Saharan African countries – Bendavid et al. (2011)

It transpires however that we are perhaps not looking at such a clear-cut natural experiment as the simplified version of 8 years on, 8 years off might lead us to believe. Direct funding of abortion services had actually already been banned by The Helms amendment to the 1973 Foreign Assistance Act, over ten years before the policy was first announced. Even then however, the perception was that the ban was stricter than it was and it has been argued that family planning organizations self-censored themselves due to uncertainty and misunderstanding about the extent of the ban. The 1984 announcement forced several organizations to explicitly forego US funding, but then in 1988 a US district court found that the policy violated freedom of speech rights of American family planning organizations, so could only be applied to foreign NGOs. In 1985 it was also made clear that the gag rule did not apply to cases of incest or rape or where the life of the mother was in danger.

In 1993 the rule was rescinded by Bill Clinton, however two years later Republicans, having taken over control of Congress, tried to reinstate the policy again but were forced to accept a negotiated 35% reduction in funding for organizations that would not comply by the Mexico City rules. Clinton was forced to accept additional restrictions in 1999 in budget negotiations with Republicans, before George W. Bush took office in 2001 and reinstated the policy in full force, therefore again banning all USAID family planning funding from going to NGOs that were not compliant. Still, two years later Bush was able to expand it further, by applying it not only to USAID funds but to all State Department grants for family planning as well. Yet that same memorandum made it explicitly clear the policy did not apply to funding for global HIV/AIDS programmes, which were considered as separate from family planning. Population Action International has consistently published clarifying brochures over the years to combat what it calls over-interpretation of the policy.

Family planning in the developing world is of course not an American prerogative and other countries have already promised to step up in the wake of Trump's announcement: e.g. the Dutch have announced a fund to counter its effects. But the most recent reinstatement of the policy is not just a repeat of the 2001 Bush executive order – it is in fact a dramatic expansion of the policy that now applies not only to family planning, but to all US global health funding. Thus it is not only in opposition to the Bush 2003 exemption for HIV/AIDS programmes, but also applies to all other global maternal and child health programmes, malaria programmes and other global health initiatives funded through e.g. the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Defense. The issue is much broader than that these agencies will not be allowed to fund programmes that promote abortion, they will not be allowed to fund any programmes that are run by organizations that have a separate (non US funded) programme that falls foul of the policy. It may also affect US funding of multilateral organisations, amongst them the UN Population Fund in particular, although to what extent is as of yet unclear.

High levels of anxiety in the international development community generally and the global health and family planning sectors specifically are therefore understandable. This isn't simply the third time a well known policy has been reinstated. It is instead the announcement of a new and expanded version of a policy which has historically gone through several iterations; been poorly understood and over-implemented; perhaps to some degree neutralised by other funders; and on whose effects we have many plausible speculations, but surprisingly little in terms of hard facts. At least on the empirical side the research community can do better and provide more comprehensive evidence of what its effects actually are. If not to change 'post-fact' minds, then at least to guide alternative funders more precisely towards the funding gaps that are most damaging to the reproductive health and well-being of women and children in the most vulnerable communities.

About the Author

Dr Maja Založnik s a demographer currently working on a joint project of the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing and the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food.

Comments Welcome:

We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.