Extraordinary measures have been taken in most parts of the world to contain the covid-19 pandemic. Most of us have had to adapt our daily lives to help slow the spread of the virus, protect the most vulnerable and limit the stress on the overall health system.

In France (where I live), a society-wide shutdown lasting over two and a half months is being gradually lifted, and many people are enjoying going out of their homes. It is striking how common mask-wearing has become, more common than during the shutdown, let alone before. As an anthropologist, mask-wearing behaviour interests me, as do comparisons between Europe and Asia, and especially the two countries I know best, France and Japan. Before France closed its border, several people told me that the only people wearing masks in Paris were Asian tourists, and perhaps they were right. The observation piqued my curiosity.

One evening, watching the news on TV, I was struck by the differences in ‘mask culture’. I watched first a French news channel and then switched to a Japanese news channel. Hardly any of the French politicians were wearing masks, but the all Japanese politicians were.

Parliamentary (Diet) meeting, Japan, during the Covid-19. Source: Mainichi Newspaper, April 1st, 2020

Assemblée Nationale, France, during the Covid-19. Source: French 25, April 3rd, 2020

Why so different? We know that the death toll from covid-19 has been much lower in Japan than in the West, and since it is at least possible that the use of masks could have contributed to this, it could be interesting to try and understand cultural logics of mask-wearing.

In Paris, at least in the early stages of the outbreak, there was a problem of access. It was not easy for the general public to get hold of masks because health workers had priority, but even so, almost no one was wearing a mask. I visited several pharmacies to try and purchase masks but with no luck. One pharmacist explained, '3000 masks were delivered this morning, but they all sold out in the morning.’ Perhaps some people bought them to leave at home ‘just in case.’ Even during the shutdown, particularly the first two months, the only people I saw wearing masks were some older people shopping in a supermarket. Now, after restrictions on movement have been lifted, more or less two-thirds of people walking down the streets are wearing masks. Prior to the shutdown, the French government and the media said that ordinary masks were not very effective against covid-19. Now there is strong messaging to encourage the people to wear masks. There are government advertisements on television and roadside notices.

In Paris, at least in the early stages of the outbreak, there was a problem of access. It was not easy for the general public to get hold of masks because health workers had priority, but even so, almost no one was wearing a mask. I visited several pharmacies to try and purchase masks but with no luck. One pharmacist explained, '3000 masks were delivered this morning, but they all sold out in the morning.’ Perhaps some people bought them to leave at home ‘just in case.’ Even during the shutdown, particularly the first two months, the only people I saw wearing masks were some older people shopping in a supermarket. Now, after restrictions on movement have been lifted, more or less two-thirds of people walking down the streets are wearing masks. Prior to the shutdown, the French government and the media said that ordinary masks were not very effective against covid-19. Now there is strong messaging to encourage the people to wear masks. There are government advertisements on television and roadside notices.

A street-poster to promote wearing of masks by Paris City Hall. Text translation: “In Paris, we don’t go out without our trendy accessory. Coronavirus: let's protect ourselves and each other. For the health of yourself and others, respect the preventative measures”. Photo taken by the author, May 2020.

For the Japanese, on the other hand, masks have been a ‘must-take’ item throughout the pandemic, but not because of government pronouncements. From the beginning many Japanese followed government guidance not to go out more than necessary - even though it was ‘only’ guidance (the government does not have the legal powers to impose widespread restrictions on movement). Neither did the Japanese government act swiftly to provide financial support (as in France and other European countries) to help cover the salary costs of employees. Eventually, after much criticism, it changed tack and provided payments of 100,000 yen per person (approximately 740 GBP). Before this, one of the major initiatives of the government was to distribute two masks to each household, as a cost of 46.6 billion yen (approximately 350 million GBP) including the package fee and shipping costs. To make it clear, that it is not two masks per person but per household. But why only two masks per household - only for parents? Or only for children? People struggled to understand the ‘Abeno-mask’ policy. And, oddly, in a country in which mask-wearing is so common anyway and masks readily available, why pursue such a policy?

The policy could be seen as a reminder of a fundamental long-standing feature of the Japanese government's approach to welfare, which is that people should look after themselves as much as possible. Post-war Japan placed economic growth as its first priority to catch up with the West, and social welfare policy took second place. In spite of its high level of economic development, Japan's welfare policy has depended more on the family, companies, and communities than the government. Japan has continued to pursue the path of ‘a welfare society’ rather than a welfare state. Different governments have attempted to deviate from this path on several occasions, but in the current economic downturn and with a super-aging population, it is no easy task to change the approach. The ‘Abeno mask’ policy symbolizes the approach of the welfare society. In other words, it is a reminder that people should rely on themselves rather than the government.

Yet, why do the Japanese wear masks? One reason is that such ideas of ‘self-reliance’ and ‘self-responsibility’ are not only central for the government but also people have internalised such ideas. In other words, the idea that in many spheres of life it is not the government that protects the citizens, but the people themselves, is taken for granted. Just as we can observe this idea of self-reliance at work in long term care policies, so we can see it also in the matter of masks.

Yet, why do the Japanese wear masks? One reason is that such ideas of ‘self-reliance’ and ‘self-responsibility’ are not only central for the government but also people have internalised such ideas. In other words, the idea that in many spheres of life it is not the government that protects the citizens, but the people themselves, is taken for granted. Just as we can observe this idea of self-reliance at work in long term care policies, so we can see it also in the matter of masks.

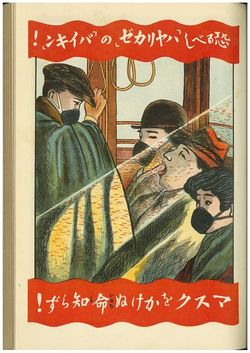

Source: A poster distributed by the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Japan at the time of the Spanish influenza outbreak. "Life threatening not to wear a mask!". The Central Sanitary Bureau, The Home Department of the Imperial Japanese Government, 1922.

Mask-wearing, moreover, is not a novelty in modern Japan. In the early Meiji era, masks were widely used to block dust. During the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, masks attracted attention as a preventative product. During 1930s and 1940s, the wearing of masks became part of an accepted social code. Someone with an (airborne) infection was expected to follow appropriate ‘etiquette’, and wear a mask. Masks acquired a cachet as valuable gifts. The wearing of masks in public places has been a part of Japanese culture for several decades now. Masks have been mass-produced in Japan since 1973 when the prototype of non-woven pleated fabric masks was first developed (the current the mainstream design). And since the 1980s it has become common practice to wear masks for the hay fever season (and pollen allergies are widespread in Japan).

Cultural notions deeply related to masks include ‘inside and outside’: uchi soto. This is something that in Japan is learned when you are very young, and the idea of dividing the inside and the outside can be seen everywhere in Japanese society. The application of the inside-outside distinction depends on context. In the family, insiders could be immediate family members, and, in other social settings, insiders could be classmates or all members of the school, just as at work they can range from immediate team members to colleagues in a department to all employees in the organization. The inside-outside distinction is used not only for relationships but also for places, such as at a national level the distinction could be Japan vs outside of Japan. In the domestic space, for instance, most Japanese houses and apartments have a space at the entrance to take off your shoes. This entrance place has about 30 cm step up to the corridor to distinguish the inside and outside of the house. Once you step up and enter the house, you wash your hands with soap and gargle. Washing hands is a practice that most people do frequently during the whole year, not just during the ‘flu season. Why? It’s not just that the germs from the outside are washed away, but that the outside is considered, symbolically, to be dirty and dangerous. In that respect, masks also create a boundary line that separates the outside from the inside (self).

Furthermore, the Japanese historically have a strong sense that they should not disturb others, as well as a sense of self-responsibility. To grow rice, households with neighbouring fields have to share water. Therefore, it is essential to get along with your neighbours. If you don't have a good relationship, you won't get enough water in your rice fields. To maintain security in the local community in the time of Hideyoshi Toyotomi Shogunate (16th century), there was a system called ‘a five-member system’: This was established for the purpose of joint responsibility, mutual monitoring, and mutual assistance amongst a group of five neighbours. There was also a form of ostracism called Murahachibu. Individuals who failed to follow local rules and the demands of good order could have their relations with their neighbours formally severed in a way that effectively excluded them from most aspects of communal life. In other words, causing annoyance and bothering other people is absolutely something that should never be done as part of communal living. In the case of covid-19, this means that people feel obliged to wear a mask not to avoid transmitting the infection to others.

Japanese attitudes to the responsibilities of communal living as well as to matters of hygiene and health have deep cultural roots, and these are manifest in daily mask use. Thus we can see how the differences in social values might help us understand how people in different places approach the covid-19 situation.

About the author:

Dr Umegaki-Costantini’is a Marie-Curie Fellow at the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing. At The Observatoire Sociologique du Changement (OSC) at SciencesPo her research is focused on elderly care and care technology in Japan and France, which is fully-funded by Horizon 2020 Marie Curie actions by the European Commission.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.