More and more consumer products targeted at older people are coming onto the market in Japan. This can be seen, for example, in the way that electronics manufacturers such Sony and Panasonic are investing heavily in the development of ‘smart’ retirement homes. What I want to highlight here, however, is a different phenomenon, the emergence or growing prominence of various occupations or ‘professions’ related to ageing. I came across some of these during my fieldwork in Tokyo last summer, and I think they provide a window into understanding broader aspects of Japanese society.

An acquaintance of mine in Japan introduced me to a man who provides advice - for a fee - on matters to do with care, that is, ‘eldercare’. I met him in a quiet cafe in a department store in Tokyo. He was in his late 30s, and greeted me courteously - ‘Pleasure to meet you and glad to share my experience with you today’. On his business card, which he gave me, he described himself as a ‘Care Consultant.’ Like most people I suspect, when I see the term ‘consultant’, I tend to think of a business like KPMG providing advice to the senior management of companies that can afford such services. The idea of ‘consultancy’ in regard to care for older relatives was new to me. Care consultants, such as the person I met, are professionals who specialize in providing advice on how to arrange nursing care for older people. Most of their clients are people who act as the main carers for parent(s) or a spouse. The services they offer include nursing seminars, often at large companies, as well as personal counselling for /individuals company employees. Although the costs vary, a typical company seminar costs around 1200 GBP per session, and individual counselling is around 170 GBP for a 2 hour session. The individual counselling fees must surely count as a significant expenditure for many of the people who pay for their services. What they hope to get is useful advice on planning and arranging an appropriate approach to care for someone who is dear to them.

The emergence of care consultancy as a new occupation prompts an obvious question - what kind of demand does this service meet and what led to the demand? In Japan, until quite recently, most of the care provided to older relatives was supplied by family members who would typically be full-time housewives looking after their husbands’ parents. Social and demographic change - the increase in women’s work force participation, changes in family relationships, and the continued increase in the number of old people themselves - mean that this model is no longer as common as it once was. The full-time housewife who also acts as a carer is being replaced by the carer who is also in full-time paid employment. Not so long ago, men who worked full-time were seen as exempt from any ‘duty’ to provide ‘hands-on’ care for older members of the family. Things have changed. ‘I am a man working full-time’ is no longer regarded as an acceptable excuse for not being involved in care.

For such family working carers (not only men of course), care consultants have become an important resource. They provide advice and information about how to deal with the various situations that arise when an older parent starts to be in need of care or their care needs change. What is striking about the function they fulfil is its close resemblance to the kind of support that might have been offered more informally in the past by someone living nearby, an aunt perhaps or neighbour. The need for advice is not new. What is new is the professionalization of the role of advisor, and it seems that change is in tune with the current situation in Japan. It has become not only acceptable but desirable to involve a complete stranger, a care consultant, a detached outsider, in what has traditionally been considered a 'family problem’ and a private matter. Why should this be? I think we have to suppose that the value of the service provided by the consultant lies not just in the usefulness of the advice offered, but also in the symbolism of an emerging profession whose activities show that care issues are no longer just private issues.

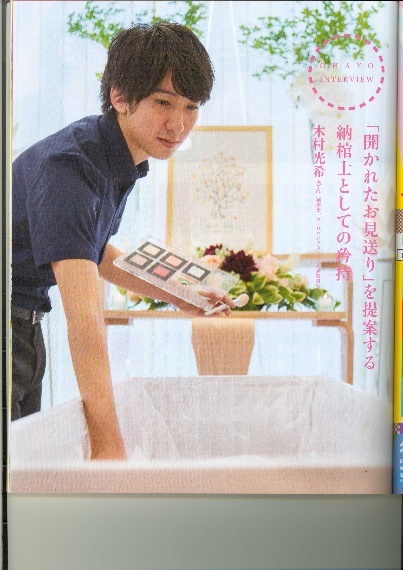

Another example of the interplay between our ageing society and the development of professions can be found with undertakers who are responsible for that part of mortuary rituals associated with the preparation of the body for funeral rites. During my stay in Tokyo, I watched a very popular TV program about professional people who are active in various fields. My attention was caught by a smartly dressed young man leaning over someone with a serious look. The on-screen text explained that he was ‘a Japanese ritual undertaker’, and he was applying make-up to the face of a deceased person. His job is to look after the corpse until the cremation, so that family and friends can see the deceased. Partly as a result of the popularity of a recent Japanese film, Departures, it has become a profession in the limelight.

Another example of the interplay between our ageing society and the development of professions can be found with undertakers who are responsible for that part of mortuary rituals associated with the preparation of the body for funeral rites. During my stay in Tokyo, I watched a very popular TV program about professional people who are active in various fields. My attention was caught by a smartly dressed young man leaning over someone with a serious look. The on-screen text explained that he was ‘a Japanese ritual undertaker’, and he was applying make-up to the face of a deceased person. His job is to look after the corpse until the cremation, so that family and friends can see the deceased. Partly as a result of the popularity of a recent Japanese film, Departures, it has become a profession in the limelight.

Most funeral rituals in Japan used to be based on Buddhist practices, which called for a very particular preparation of the body, including ritual washing and closing of orifices. The undertaker would take care of the presentation of the body for viewing, which typically included dressing the body and attending to its appearance, and this might include the application of make-up. The undertakers who performed this work used to be considered ‘unclean’ and socially ‘untouchable’. This reflected a traditional association of death with defilement. This history is quite at odds with the current popular attention being paid to the work of undertakers.

There has also been a significant change in the selection of funeral venues in the last few decades. Up to 1990, the majority of funerals were still performed ‘at home’ (i.e. in a private house). By 2011 things had changed, and 80% of all funerals were performed in so-called ‘funeral halls’. In the mid-1990s the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare started issuing licences for ‘Funeral Festival Directors.' Along with the licences came a qualification system to ensure an appropriate level of knowledge and skills. The number of people who have this qualification has now reached 35,590 people, although it is not necessary to have the qualification in order run a funeral hall. Japanese society places a high value on qualifications, which may explain why the licencing system helps attract people into the work.

As for the undertaker who was featured in the TV program, in 2013 he founded the ‘Okuribito Academy’, whose students, mostly young people, learn how to make life's ending better and more meaningful (and gain the appropriate qualification). As well as being director of the school, he is also much in demand as a public lecturer, and his achievements have become sufficiently well-known to attract the attention of overseas media. His career is emblematic of the ways in which Japanese culture is shifting alongside rapid population change. Traditional ideas and rituals are no longer as dominant as they once were.

In the past, family members would have been much more likely to follow local customs and practices propagated through informal networks and established services or institutions. The question of how to care for older family member or how mark a death received a ready answer. The appropriateness of the associated practices was taken-for-granted. Now, with the increasing professionalization and commercialization of such services, individuals are encouraged to choose providers. They consult with these providers to see how they might exercise control over the form that a service will take, and in so doing take help to reshape cultural norms and practices.

Source of the photos:

The first photo: https://okuribito-academy.com/news/detail.php?id=26&gi=0

The second photo: https://okuribito-academy.com/portfolio/gallery/

About the author:

Dr Umegaki-Costantini’is a Marie-Curie Fellow at the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing. At The Observatoire Sociologique du Changement (OSC) at SciencesPo her research is focused on elderly care and care technology in Japan and France, which is fully-funded by Horizon 2020 Marie Curie actions by the European Commission.

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.