The gender pay gap is not a good measure of gender discrimination. The attention it is being given is disproportionate and misleading. If it leads to companies gaming it, its effects could be extremely counterproductive. It might improve for reasons that have nothing to do with improving the lot of women, or improvements in it might come at the expense of much more deprivileged groups in our society. On balance the introduction of mandatory reporting is probably harmful.

Intro

For the past few weeks British companies and organisations with over 250 employees have been uploading their gender pay gap figures onto a government data platform, scrambling to meet today’s deadline, or face unlimited fines.

These openly available data have been of considerable interest to journalists and the public, who have been analysing the numbers more or less thoughtfully (if they got beyond just bandying about headline figures of what they deem particularly gross offenders). I have no reason to doubt the good intentions of the legislators mandating the gender pay gap reporting, or the honesty of the dismay and outrage being stoked by the media in response to the results. But I have good reason to believe that the gender pay gap is very poorly suited to tackle gender discrimination in the workplace.

The main reasons I want to try to flesh out here are:

- People confuse the gender pay gap with unequal pay;

- The gender pay gap is an artefact of forces other than gender discrimination, specifically labour force participation rates;

- There is a danger of the gap becoming victim of Goodhart’s law: when the measure becomes the target and therefore ceases to be a good measure.

- Other unintended consequences.

(Of all the issues with the gender pay gap that come to mind, these are the more statistical and methodological ones, so the fact that I am not a labour economist, should be irrelevant.)

What is the gender pay gap being reported?

First of all, let’s be clear on something: men and women doing the same work in a company must receive equal pay. This is a legal requirement in the UK, and has been since 1975. It is however not uncommon for people to be under the impression that that is not so, at least in part due to headlines decrying the fact that British women are being “cheated” or “short-changed” by their employers; or advocacy groups publicising the so-called Equal Pay Day, which is a day in November after which “women effectively work for free”. Even sloppy language such as “[most] companies pay their male staff more than their female staff”, while technically true, is terribly misleading as it will be interpreted by most as describing unequal pay for equal work.

These are therefore examples conflating wage discrimination—which is illegal—with the gender differences in the jobs that people choose—which may be caused by gender discrimination, but also by differences in education, skills, personal preferences, social and cultural norms, access and opportunities, responsibilities, levels of risk aversion and forward planning, and other demographic characteristics such as age, ethnicity etc. Like I said, I am not a labour economist, so I won’t go into too much detail here, but to mention that research that has tried to control for as many of these factors as possible, has actually found most of the gender pay gap disappear [1]. And to be clear: I am also not here to claim that gender discrimination does not exist or that gender stereotyping is not harmful, simply that the gender pay gap is not a good measure or target if we want to work towards a more equitable society.

So what are British companies required to report? First of all they have to report the difference in the mean and in the median of the full-time hourly wages they pay to their male and female employees. Reporting both the mean and the median is important since wage distributions tend to be right skewed, so just the mean can be misleading, while the median is meant to better represent the typical employee. Only full-time employees are counted [2] and the calculation is done on hourly rates in order to avoid issues with (men being more likely to work) overtime.

So for example we can check my employer, Oxford University, to see that full-time female employees’ average hourly rate is 24.5 % lower than that of males, while the median rate is 13.7 % lower. Again, this is not because it is paying men and women different rates on the same positions, but because there are more men in the higher paid positions and more women in the lowest ones.

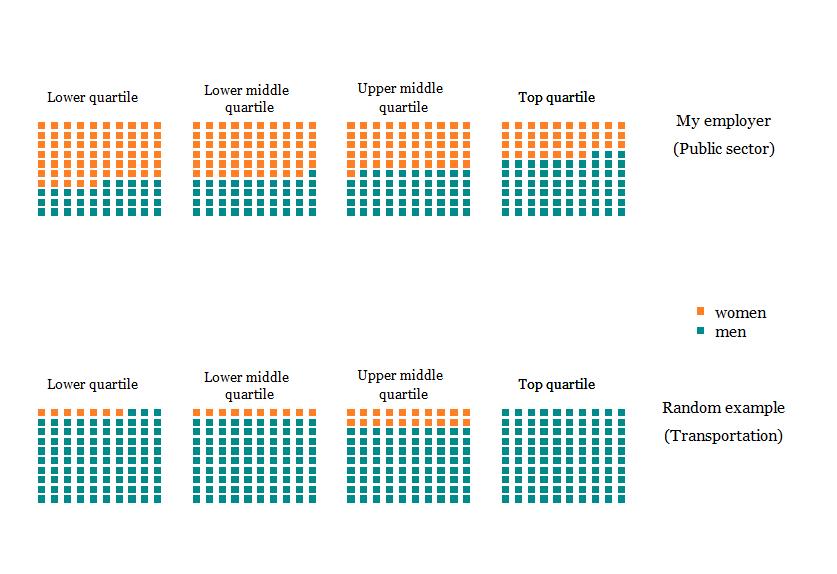

We know this because additionally each employer must also report the gender ratio in each of the four pay quartiles i.e. of the lowest paid 25 % of employees, how many are men and how many women, similar for the next 25 % etc. This distributional information gives a bit more context to the headline figures mentioned above. And as you would expect, it varies dramatically between companies and especially between sectors. For example in Figure 1 below you can compare the distribution at Oxford (top), where there are more women than men in the bottom three quartiles, and the distribution in a random company from the transport sector (bottom), where there are very few women at all, but the ones that are, are mainly in the third quartile (this company actually has a negative gender pay gap i.e. women on average make more than men).

Using only the information provided it is of course impossible to tell if either of these companies is in breach the Equality Act (although they are probably not). Nor can it be determined if any other type of gender discrimination is taking place or what should be done to avert it.

Figure 1: Example gender distributions in each quartile for two organisations Source: https://generd-pay-gap.service.gov.uk (accessed 3.4.18)

The gender pay gap is sensitive to things other than gender discrimination

So the gender pay gap—regardless if it’s median or mean—does not track with wage discrimination. What it does track is women’s expressed preferences. Which means it is a grossly simplifying aggregate statistic describing the incredibly complex intertwining of opportunities and choices. And yes, also of discrimination, but it is not even obvious that an increase in discrimination would necessarily lead to a larger gender pay gap. But we’ll get to that in the next section, first there is a broader point to be made.

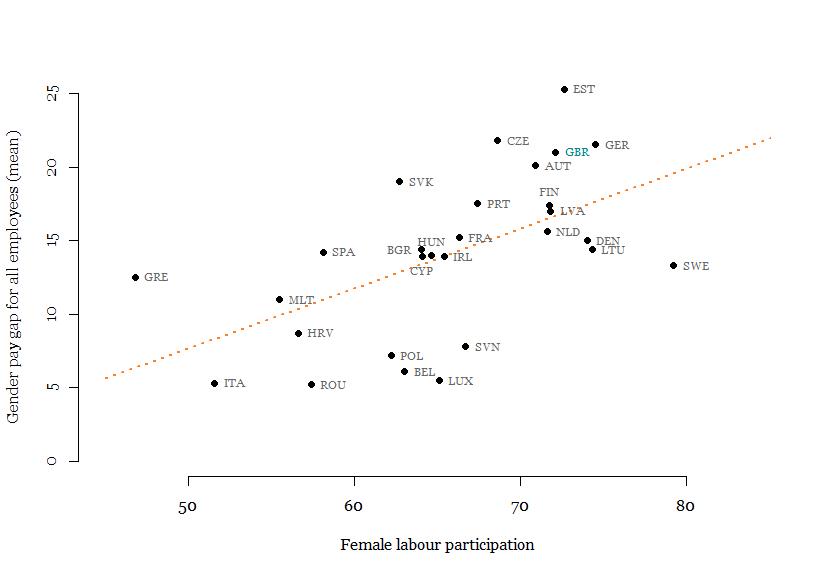

At the risk of stating the obvious: let’s start with the fact that the gender pay gap applies only to women who are employed. And women who are employed differ from women who aren’t economically active on a whole range of dimensions. So what do you think tracks strongly with the gender pay gap? Exactly: female labour market participation. It turns out that countries with low levels of female participation—and the concomitant lack of flexible working arrangements, generous maternity leave and pay etc.—are also the ones where the gender pay gap is the lowest. Figure 2 below shows the most recent data for the EU countries, and the correlation is quite clear.

As counter-intuitive as that may seem at first sight, it makes sense if we think it through: high participation rates for men mean they are represented on the whole range of pay rates, from the lowest to the highest incomes. Lack of flexibility in the market makes it less enticing for low-skilled women to join or less worthwhile for employers to take on the costs of hiring them. This means the women who are working are more likely to be better skilled and better paid than the average woman, which shifts their wage distribution higher than if their participation had been at the same level as that of men’s.

Figure 2: Gender pay gap (mean) and female labour market participation (20-64) in EU countries. Source: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ (accessed 30.3.18)

At the extreme end of the spectrum is this nugget: about ten years ago the data showed the smallest gender pay gap (most in favour of women) was in, wait for it, Bahrain. Yes, apparently in 2008 the pay gap there was a whopping negative 40 percent! This was of course entirely due to women being almost completely excluded from the economic life of the kingdom, but the ones that did take part were very highly skilled and in well paid jobs. Of course not an ideal anyone would want to strive for.

But even without the extreme outlier that was Bahrain, the lesson is still there: crucial for the understanding of the gender pay gap is the composition effect. Changes in the composition of the workforce will have effects on the gap that might not be intended. Yes, increased levels of education for women will tend to decrease the gap (provided these women choose to take advantage of it). But e.g. better conditions for maternity leave and increased flexibility of working hours, things that we probably all agree are desirable, might bring more low-skilled women into the workforce, women for whom it wasn’t worthwhile to work before. And the unequivocal effect that would have on the gender gap? It would of course increase it.

Goodhart’s law much?

I hesitate to use Goodhart’s law in this case actually, because the underlying idea of the law is that the measure must have been a good one at some point in time. But as we have seen, the correlation between the gender pay gap (the measure) and gender-based discrimination in the workplace (the target) crucially depends on the degree of labour force participation, so it was never really a good measure to begin with.

But now it has also become a target, with the government mandated reporting, and with the media eager to publicise headline figures and less eager to provide nuanced context. And once it becomes a target, companies are presumably expected to show progress in closing the gap. Closing the gap is not actually a requirement of the bill, although Labour has pledged that they would impose sanctions on companies that failed to comply. This, alas, would be incredibly foolish.

The reason is simple: on the most basic level, there are two ways you can reduce the gender wage gap: either employ more women on posts with above average incomes, or employ more men on posts with below average incomes. So a directive to close the gap actually provides a perverse incentive to discriminate against low-income women. I thought I’d give you a visual as well, so have a look at the gif below. It shows a made up company (I picked the quartile distribution from the reported data), and I added a hypothetical income distribution [3] below. I’ve added the lines to represent the median and mean incomes (full and dotted lines respectively) for men and women, as well as printed out the value of the gap.

So what is my fictional company doing? One by one it is firing the lowest paid women and replacing them by men on the same positions. And what is happening with its gender pay gap? Yup, it is decreasing, exactly as was the goal. Or was it?

.gif)

Figure 3: Hypothetical example of closing the gender gap by firing all the low-income women and replacing them with men. Source: author’s calculation.

This is of course a massively dramatized example, but it exposes a real problem with the gender pay gap that HR managers around the country will be faced with soon enough. Sure, you can easily imagine the intended consequence of the bill: a company advertises for a highly paid position, shortlists two equally suitable candidates who differ only in gender. It should of course hire the woman, and therefore decrease its gender gap. But what if the job is in its lowest income quartile. An equally suitable man and woman apply. An unscrupulous employer might already be worried about hiring a woman that might require more time off or flexible time to care for her children, but using that as a hiring reason would be illegal. But decreasing the gender pay gap can give the decision to hire the man over the woman a nice boost.

Instead of incentivising employers to improve working conditions for women who need it most—those at the lower end of the income ladder—a policy aimed at closing the gap could have the exact opposite effect and make those women less attractive to employers.

Other unintended consequences

In addition to companies directly gaming the system as described just above, there are other unintended consequences of declaring closing the gender pay gap as a desirable outcome. As noted before, the pay gap applies only to women who are in the labour force. So any benefits that were to accrue to women would go disproportionally to the group with the highest labour participation: white women. Thus reducing the gender pay gap will most likely exacerbate the ethnic pay gap. This makes sense, as focusing solely on one dimension of discrimination (gender) that is not aligned with others (ethnicity or disability) is unlikely to be neutral for the latter. This is true regardless of which group you think is most discriminated against, or how you feel about the importance of intersectionality.

Because different subgroups have different labour force participation rates, closing the different gaps will by definition come into conflict with each other. For example let’s look at closing the ethnic pay gap for Bangladeshis. A good thing, no? But because Bangladeshi women have a participation rate of about 37 %, most of the benefit of closing that gap would go to Bangladeshi men. So at the national level this would manifest itself as a widening of the gender pay gap. Is that then a bad thing?

Here's another compositional effect: age. The UK is in the last stages of aligning the pension age for men and women. This means women are staying in the workforce longer that they had, which has an effect on the composition of companies. In sectors where there is a premium paid for seniority, that might mean these women’s pay checks contribute to closing the gender gap. In sectors where older workers tend to be low-skilled and lower income, keeping them in the workforce longer will increase the gender pay gap.

These are just some of the myriad of factors that affect the headline measure the government is now mandating. I’m not sure how much of an administrative burden it is for the companies to prepare the data and report it, presumably it is not too arduous. And I do love open data, so the fact that I oppose this reporting should tell you a lot. Because despite its laudable goals, it puts companies in the position of having to justify themselves to the public and the media who have grabbed a headline figure that they do not fully understand. That is bad enough. But if closing the gap ever became sanctioned, that would directly harm some the most vulnerable groups in our society.

The gender pay gap is not a good measure of gender discrimination. The attention it is being given is disproportionate and misleading. If it leads to companies gaming it, its effects could be extremely counterproductive. It might improve for reasons that have nothing to do with improving the lot of women, or improvements in it might come at the expense of much more deprivileged groups in our society. On balance the introduction of mandatory reporting is probably harmful.

[1] For a couple of accessible summaries (from slightly different points on the ideological spectrum) I suggest the write-up by Our world in data, the ONS’s write up, and the slim volume from the Institute of Economic Affairs

[2] However when reporting the gender gap for bonuses, which I don’t discuss here, employers must include part-time employees. And since many more women work part-time than men, this leads the bonus figures to overestimate the gender gap. The reasoning behind choosing such guidelines for reporting is not clear to me. Nor is why they did not also require companies to report part-time gender gaps as well (which often favour women i.e. are negative).

[3] This is a very crucially missing bit of information when assessing any of the reported data: intra-company income distributions are where all the nuance lies, and I found it impossible to get access to such data anywhere. So as a kludge I just used national level data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings 2015, which is of course pretty unrealistic for a company, but probably more realistic than anything I could have made up myself, and doesn’t affect the point I am trying to make anyway.

* All data and code are available at https://github.com/majazaloznik/gender-pay-gap

About the Author

Dr Maja Založnik is a demographer currently working on a joint project of the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing and the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food.

Comments Welcome:

We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.