The Resolution Foundation published the final report of its Intergenerational Commission in May. After a flurry of predictably mixed responses in the mainstream press, we have to wait and see whether either of the main political parties picks up the issue in its next election manifesto. Who would bet on the present government doing anything before then?

The report argues that the dice are loaded against young people (call them ‘millennials’) when it comes to securing what we have come to regard as basic goods. They are leaving university with a large debt (unlike their parents - who were also much less likely to attend university, especially if female) and it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to buy a home (the ratio of house prices to incomes has doubled in the last 20 years). They are adversely affected by stagnation in wage growth and have serious concerns about future demands that might be made on them as taxpayers to finance age-related services - especially social care. The pension age is going up and defined benefit pensions are becoming ever thinner on the ground. Bundle all these issues together and it can be argued that their lifetime prospects (measured in terms of indicators such as opportunities for wealth accumulation) are not as good as those of their parents; or at the very least they have not improved. This is why an editorial in the Financial Times thought that young people should “make their anger felt at the polls” if their concerns are not addressed soon. The Observer went further with a strapline declaring that “It’s time for Britain’s millionaire pensioners to pay up”.

So what grounds can there for objection? Some critics (not many) took issue with the ‘diagnosis’. Others accepted the ‘general thrust’ of the diagnosis but took issue with some of the more eye-catching policy proposals, especially the ending of exemption from National Insurance payments for people continuing to work when they are over 65 (reduces incentives to stay in work) and a conditional cash transfer of £10K to be paid to all citizens on their 25th birthday. Although this is unquestionably a lot of money, it’s not enough to pay off the average student debt or put a deposit down to buy a house (and if these are the main problems, it is easy to argue that this is not much of a solution). There are, however, other proposals besides these, including an overhaul of inheritance tax (with a view to reducing exemptions and increasing revenue). There is of course an obvious reply to critics who fix on particular proposals - come up with better proposals if you think that the basic diagnosis right.

And this brings us back to the diagnosis. The whole point of the report is to treat a number of specific policy challenges as part of a wider problem that is cast in generational terms: the ‘generational contract’ is under strain and it is the job of government to sort it out; our polity has to find remedies for the emergence of a worrying level of generational inequality - worrying because of its effect on the political sustainability of the ‘generational contract’. The nature of the problem is such that the essential remedy has to be some form of generational redistribution in favour of the young.

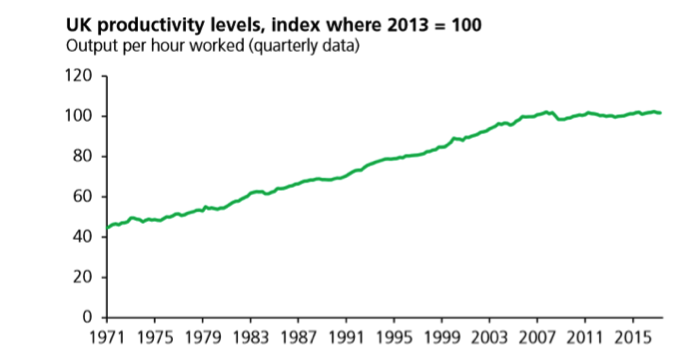

Like Martin Wolf in the FT, I am skeptical about the idea of a generational contract, or rather I am skeptical about how hard it can be pressed. Because the contract is ‘implicit’, it is also indeterminate. We can argue about what count as legitimate expectations among young people (or older people for that matter), but we can’t point to a contract to settle our disagreements. Take, for example, the expectation of ‘generational progress’, “that each successive generation should have a higher standard of living than the one that came before it”. Without productivity growth, this is hard to achieve and few people would doubt that the UK has a major problem with labour productivity. But is this part of the ‘generational contract’? To which we must ask whether this is really a useful question. It’s hard to disagree with Martin Wolf on this point at least. “It all has to start with economic growth. If growth performance does not improve, the world of ever-rising fortunes will be gone forever”.

Source: House of Commons briefing paper 2017

The whole point of the report is that the case for bundling together the various issues it highlights is different from the case for regarding each of these issues as a serious and challenging policy problem in its own right. It would be a mistake therefore to dismiss the idea of a new generational contract as just packaging (i.e. a good way to attract public attention for a number of issues that bear down hard on younger people). At the very least, we should consider the argument that our society cannot engage with at least some of its emerging problems without making use of the idea of generational fairness.

If, however, we ask which problems can be usefully analysed in these terms, some of the grievances highlighted by the report surely don’t fit the bill. Housing? Doesn’t this boil down to a problem with supply? Wage stagnation? Hardly. Student loans? Arguably the fairest way to finance a large-scale expansion of higher education, even if we think that there are serious problems with the ‘parameters’ (see Prof Nicholas Barr). The case for treating the reform of social care funding in generational terms is more plausible, given that the nub of the problem is how to expand public provision in a sustainable way. It is reasonable to insist that government should to take into account the generational incidence of the costs associated with increased provision. And as for changing patterns of pension risk, it is hard to argue that the so-called ‘triple lock’ on the state pension is not generationally unfair if we suppose that it was introduced as a sweetener for older voters.

It is one thing, however, to require that welfare reforms should be judged by a standard of generational fairness, and quite another to make a case for generational redistribution. At the heart of this report we can discern the shadow of David Willetts’ book The pinch, and like the book, it has to be seen as an argument for generational redistribution. The £10K cash transfer is an essential part of this, and we should evaluate it not by its effectiveness in solving a problem that affects young people (not enough savings and house prices too high) but as a remedy to a generationally unfair division of wealth gains from house price increases. The pinch argues that some of the windfall gains that an older generation (he called them the baby boomers) has made from increasing property prices should be redistributed to what we may loosely describe as their ‘children’s generation’ and that government should take a part in this. What we are given is not a moral argument for private intergenerational transfers (parents have an obligation to make provision for their children), but a social justice argument for public intergenerational transfers. But is the case for taxing these ‘windfall’ wealth gains really dependent on the generational format in which it is cast? Why not argue that anyone making windfall gains from house prices irrespective of age or generational provenance should be taxed accordingly? And why not use the proceeds to improve public services for everyone?

About the Author:

Kenneth Howse is a Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing. He is also a key member of The Collen Programme on Fertility, Education and the Environment.

Opinions of the blogger is their own and not endorsed by the Institute

Comments Welcome: We welcome your comments on this or any of the Institute's blog posts. Please feel free to email comments to be posted on your behalf to administrator@ageing.ox.ac.uk or use the Disqus facility linked below.