Blog

Latest

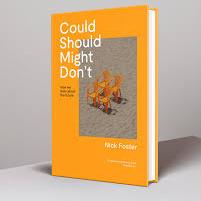

Four ways to think about the future

Researchers routinely invest enormous amounts of time and effort in trying to figure out the future of products and services for the societies of tomorrow. Whether they’re engaged in scenario...

Beyond “Blue Monday”: The Real Science Behind Winter Wellbeing

I was born in Whitehorse, Yukon, where winter isn't just cold; it's dark. It's really dark. At 60.7 degrees north, daylight fades quickly. By December, the sun barely rises before it si...

Walking With My Grandmother: What Older Adults Have Taught Me

I grew up with my Italian grandmother. When I think of my childhood, the most vivid memories are of walking with her to small grocery stores, stopping to listen to her conversations with the owners...

A Rewarding Academic Journey: Reflections from the Oxford Short-term Exchange Programme on Demographic Change

The Oxford Institute of Population Ageing hosted the Short-term Exchange Programme under the theme “Using Data to Understand Demographic Change” from 15 to 19 September 2025. ...

The baby-boomers versus the baby-busters

This has been a Summer of Discontent according to various commentaries. The discontent, defined along an intergenerational divide, amounts not so much to a conflict as to an outright war. ...

Caring in Couples: How Spousal Characteristics Shape Unmet Care Needs in Later Life

Introduction As England’s population ages and formal social care services struggle under growing policy and funding pressures, family caregivers—especially spouses—have taken o...

The Compleat Ageing Angler: Reflections on Fishing, Family, and Flourishing

As academics, industry leaders, and policymakers explore innovative approaches for promoting health and well-being across the life course, renewed attention to outdoor activities offers a...

Where next for ageing and AI in its hardware phase?

As 2025 shapes up to be the year that Artificial Intelligence really goes mainstream, even America’s new Secretary of State for Education is sitting up and taking notice of AI. Or A1 (A One),...

Grey areas: What does it mean for research on older workers when DEI takes a back seat?

In recent years, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) frameworks have gained prominence across academia, policymaking, and commercial organisations. The application of these frameworks aims to en...

Population Ageing in Taiwan and the role of AI to address the challenges

Over the past five years, Taiwan has drawn global attention for its contributions to high-tech industries and its ability to navigate global supply chain disruptions. Yet, beyond its economic and t...

Ageing & Faith: A Sacred Search for Significance

Rome, Jerusalem Haifa, Mecca, Fatima, Bodh Gaya, Haridwar, Amritsar, sacred trees…images of the ageing journeying through these sacred spaces flit across my mind. Sacred means awe and revere...

Rewriting Ageing: Bob Dylan and the Legacy of 'Forever Young'

In November 2024, I attended a Bob Dylan concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London. The reaction to my enthusiasm for seeing Dylan live from my social circle ranged from astonishment to scepticism...

The Substance: Highlighting Ageism and Beauty Norms in Contemporary Cinema

Note: This analysis contains minor spoilers about the film. This blog post explores the 2024 film The Substance, directed by Coralie Fargeat, as a critical commentary on the societal pressures f...

Family Day, Changing Families: Ageing, Care, and Fertility Decline

The third Monday of February is observed as "Family Day" Day here in British Columbia, a holiday meant to celebrate the importance of family in our lives. But as I reflect on what ‘...

Questioning the Drive to Scale up for Growth

Unless you’ve been hiding in a cave, you won’t have failed to clock the core mission of the UK Government. It has been shouted from the rooftops: growth, growth, growth all the way. Wit...